A refugee camp, especially if you’ve never been to one, probably sounds like hell on earth: crammed with unwashed, desperate people living in flimsy, flapping tents, surrounded by insufficient, filthy toilets, human waste, mounds of stinking rubbish, rats and snakes, while forced to wait in long rowdy queues for barely edible food packages. The whole scene is framed by either glaring, unbearable heat and parched earth, or else cold rain and waterlogged mud. At night women are raped: during the day people try to sleep just to pass the time.

Through my work, I’ve been to quite a few refugee camps, formerly in central Africa and recently on the island of Samos, where I’ve been working with a group of volunteers who support refugees stranded in a camp on the island. The description above is crude, but it’s also true. I’ve left camps, including the camp on Samos, swallowing tears at the conditions people are forced to endure. I’ve listened to personal stories I wish I hadn’t actually heard, because they still sometimes haunt me. I’ve raged at the mind-numbing boredom that literally drives people insane as they wait for something better to happen. People commit suicide in refugee camps because dying is easier than trying to keep living.

In Africa, and Europe, people continue to die to reach refugee camps. On March 7th, a pair of four-year old Afghan twin brothers drowned when the boat they were on, heading to Samos, capsized in open sea: the body of their father was found the following morning. Just yesterday (March 12th) the body of a nine-year-old girl refugee was found on the isle of Lesvos. It’s believed she had been missing for a month. As the refugee advocacy organisation Help Refugees, puts it, “How far will we go to protect our borders? How many children will we abandon before we come to our senses?’

But

If we end the story here, not only does nothing change, but we sink into bitter sadness – and anger – and we miss something really important, vital even. Despite the horrors of the sea-crossing, and the appalling camps awaiting those who do make it, there are refugees in Greece (and everywhere else you find these camps), who decide they’ve had enough of this shit, and start changing things themselves, taking some control over their lives. In Samos, I saw young African refugees negotiating with the camp security guards, standing their ground calmly, demanding their rights. I saw older Afghani men, fed up with the stink of trash in their section of the camp, mobilising their neighbours from many countries to clean it up together, so their children could play on a cleaner patch of open ground. Women and men from different African countries have set up a makeshift church just above the camp on Samos: they hold a mass every morning together, their voices floating down the hill at dawn to the awakening harbour town.

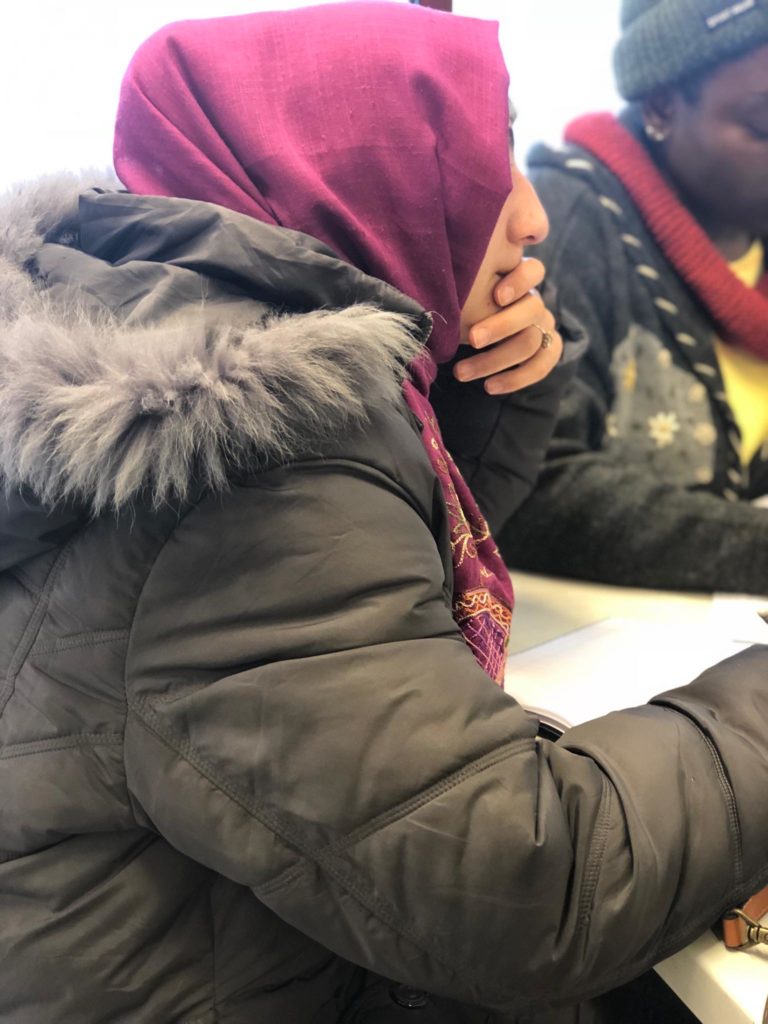

During my time with Samos Volunteers (SV), I agreed to teach intermediate adult English: teacher: my students, women and men from Afghanistan, Cameroon, Iraq, Iran, Congo, Yemen and Syria, made me giggle every day. I made up competitions, and remember being breathless with laughter, as they rowdily competed to win. One team called themselves “Supermen,” another “The Queens” (though most of them were men!). A third decided they were “The Sensible Students”! One morning I asked how they were coping with daily life. One woman said to me with heart stopping earnestness, “Teacher when I am here in this class every morning, then everything is okay.”

This is what the Canadian writer Yann Martel calls “the better story”, the glinting underside of a dark slab, where concrete actions create changes to cruel daily realities. There are places in this mad grief-stricken world where we can still improve people’s lives by being alongside them: where a group of unpaid volunteers can run rings around international organisations, because they can, and do, respond more quickly, and just get on with the work on the ground.

Samos Volunteers works on the frontline, directly with the refugees on the island: the team is mixed between volunteers mainly from Europe and refugees from many countries: we teach classes together, run a resource centre together, plus kids’ activities twice a day on the patch of hillside the Afghanis and their neighbours recently cleaned up. SV also has a small mobile library (nothing fancy, a few boxes of books in Arabic, Urdu, Farsi and other languages, a portable table and a big note book for lenders to sign – what else do you need?). There are women-only activities, evening sports classes, art classes and computer classes. There’s also a laundry station, the only place on Samos where refugees can wash and dry their clothes when the weather is wet and cold. And there’s a lot of laughter. Because, unpaid, overworked and sometimes overwhelmed, we are doing something to be proud of every day.

I’ve seen the impact of these actions with my own eyes. I know it doesn’t change the “big picture”, and there needs to be “bottom-up advocacy” and a strategic challenge to the EU’s ferocious migration and refugee policies: this is all utterly true. Nevertheless, what SV does is prove by its actions the simple truth that dedicated volunteers (most with no previous humanitarian experience) can work effectively together with forgotten communities, and get shit done. SV does meet with some political decision makers, who are often stunned by what we’ve managed to do and continue doing. Now other organisations are finally arriving on Samos, the network of support is growing, with new medical, psychological and material resources, almost all of them run by other volunteers.

Samos Volunteers is the better story, and you can be part of it (click here for the website, to consider volunteering if you’ve the time, or a donation of whatever you can give). An old friend of mine, in his mid seventies, is on Samos right now, with his 35 year old daughter, teaching and holding shadow puppet shows for the kids. “Another day, another challenge!” he writes hastily, “it’s awe-inspiring… thank you so much for showing us the way to this place!”