We drove across central Kyiv early on a Sunday morning. I remember being surprised by the hush: the night before the bars and restaurants had been pretty packed. But now the city was near silent, just us and a few street sweepers with their wooden brooms, though the streets already looked clean. We parked up to wait for someone. As we smoked three joggers trotted past: one was a chunky looking middle-age man wearing a day-glow green tracksuit that hurt my eyes. When I crossed the empty street to buy a coffee, the sleepy vendor was Turkish.

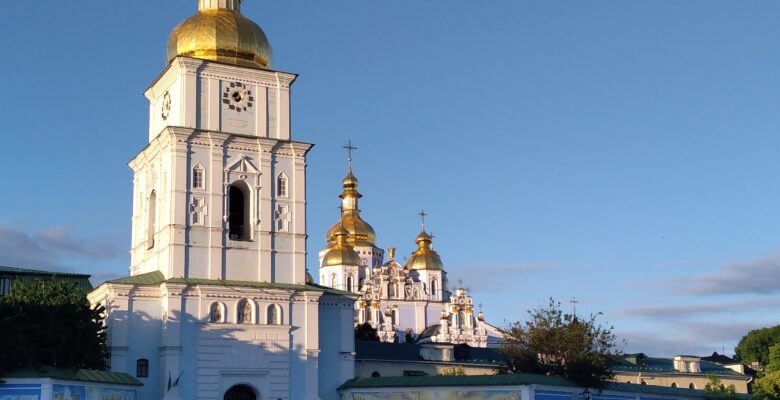

We’d spent the weekend partying in Kyiv; Georgian food, buttery croissants, wonderful coffee. And strong cocktails. Especially in the last bar, Pink Freud, where the barman was a dandy with great, gallows jokes about the war. I fell a bit in love. This a stunningly beautiful city, away from the dank suburbs of grimy tower blocks, that is. Around central Midan Square, with its glittering church roofs (this photo was taken late afternoon), Kyiv is all cobbled streets, café’s where you get the Wi-Fi password with your flat white, a lively tourist market selling miniature Ukrainian flags and hand-painted ceramics from Crimea. Nearby, the Saint Sophia Cathedral sits in well-tended gardens where I met a local musician strumming his guitar beneath a flowering tree. It was all quite trippy, after a month of living in a warehouse and visiting heavily mined villages gutted by Russian tanks.

I spent most of my time in Ukraine based in a town called Pryluki, 140 km North-East of Kyiv. I was working with a Nordic aid organisation that recruited volunteers to distribute food and hygiene kits to rural communities who had received no other assistance. The Ukrainians we met wanted soap, toothpaste, shampoo and adult diapers. Most of all, they wanted tools to repair their homes – if their homes were still standing. I was amazed how many people had stayed in their villages despite being bombed, or enduring tank battles and invasions of their homes. Many told us they had been too scared to flee when the Russians invaded; they’d seen soldiers shooting others who attempted to escape.

Low-budget horror film

It’s not so much the places but the people that I carry around with me afterwards: in the village of Yahidne I met the local school janitor, a kind man with a red face who hung around us as though he didn’t know what else to do with himself. The school was ruined; windows blasted out, classrooms filled with rubble, smashed up equipment and toys. Russian soldiers had used the school basement to imprison 350 villages for more than thirty days, including eleven children. Eighteen people died in that basement, and they couldn’t all be moved, so people slept amidst the corpses. It was the janitor who showed us the names of the dead scratched on the basement walls. The children had drawn pictures too, of their homes outside. When we clambered back out into the sun, I was clutching the janitors hand. I don’t know if I was holding onto him, or him onto me. I couldn’t quite believe what I’ve seen, it was like something out of a low-budget horror film. When we walked around Yahidne, the sense of trauma was like a cloud pervading everything with its long, chill fingers.

In one of Yahidne’s neighbouring villages, I met a woman about my age. Ludmila was standing beside the pile of rubble that used to be her home. It had been hit by several Russian missiles, leaving one interior wall standing intact and lonely. She was staring at the rubble, her face blank, eyes empty. I hugged her and we stood together in silence looking at the stones and the strewn mess. After our distribution, we drove back past Ludmila sitting on a bench outside her yard, head in her hands. We had run out of items to distribute. Some people didn’t even have clothes to change into. Since Russia’s invasion, more than 120,000 homes have been destroyed or damaged.

We had to move around these villages carefully, because they had been heavily mined by Russian soldiers. There were regular explosions, as hidden bombs detonated, or Ukrainian troops blew them up. Ukrainians told us they were scared to harvest their crops. Pryluki town where we camped out in our warehouse (I spent a month sleeping beside a wall of cereal boxes and bottles of vegetable oil) hadn’t been invaded, or mined. But one morning three missile strikes boomed nearby one after the other. We spent that morning in the warehouse bomb shelter, jittery as the sirens went off again and again. I took up smoking again, and only quit when I crossed the border back into Poland.

Our new normal

I didn’t see a single Russian soldier in Ukraine; we were quite far from the front line, which of course has shifted. But I did see a hell of a lot of burnt-out Russian tanks, including in Kyiv’s Midan square, where the authorities put them on display, to bolster local morale and show off Ukraine’s military wins. Sandbags were repurposed into sculptures, and Ukrainians clambered over them and the tanks, taking selfies.

I climbed onto a Russian tank once, on the way back from one of our visits to Yahidne. It was lying burnt-out in a field. I was with one of our translators, Mikhailov, who comes from central Ukraine, and lives in Kyiv now. “At the beginning of the war we were terrified” he told me as we stood atop the tank, smoking. “It’s amazing how much you get used to this,” he shrugged. “Our new normal.”

If I’m honest, I wasn’t really comfortable standing up there, especially when one of the volunteers, a US military veteran, told me the three Russian soldiers inside the tank must have been evaporated by the explosion. It wasn’t my victory; but it did make a good photo.

I spent less than two months in Ukraine, and have no desire to be another ten-minute expert on the war. But I did ask myself what I learnt there? Well, that Ukrainians are tenacious, won’t give up, or in. That their country is way more beautiful than I’d imagined, with its green and black fertile land, wide tree-lined avenues and gold domed churches. And that international organisations have been spread very thin on the ground (I saw one UN mission and one international NGO in 6 weeks). Local organisations seem to do most of the work in the hot zones, including psychological support for the carnage people are living through, including women and girls being raped and having their teeth kicked out by Russian troops. I still ask myself why women are punished so savagely during war.

Creative ways of killing

One more thing; the foreign volunteers who come to Ukraine include a fair number of would-be fighters / adventurers. More than in any other military conflict I’ve witnessed – and I’ve spent a good part of my professional life in conflict zones – I met men, young and older, who’d arrived with their own bullet-proof vests, and were roaming Ukraine looking for a cause to fight for, and to get a piece of the action on the frontline. These included paramilitaries and ex-Marines who were all too keen to show me creative ways of killing people. The Ukrainian Legion was inundated with applicants.

After I left Ukraine, stayed in touch with Mikhailov. We started exchanging messages regularly after the conflict intensified again a couple of months later. He was working with journalists and filmmakers, and told me he was doing okay. “You know, now I’m less afraid and more angry” he told me via WhatsApp last week. “The thing I’m really proud of is that I was involved in the making of this documentary about Mariupol.” Here is the link to, Mariupol, the People’s story.

There’s no neat way to wrap up a post about Russia’s war on Ukraine: one of my political heroes, Patrick Cockburn (who writes for the Independent newspaper) regularly offers deeper analysis of how things are going. “So far [it] looks more like the First than the Second World War in that it is likely to be long and indecisive“ he said recently. Adding that, “Neither Russian or Ukrainian is likely to win a total victory although both have the will to go on fighting in the hope of doing so.” Patrick points out that, despite Russia’s military machine blundering from defeat to defeat, “there are plenty of countries in the world to see Russia as a counterbalance to Western hegemony and will not want to see it removed as a powerful piece on the international chess board.”